Is That Sponsor’s Amazing-Looking “Skin-in-the-game” Real? Or Is It an Overinflated Ruse?

- Aug 14, 2023

- 6 min read

Requiring a sponsor to invest side-by-side with investors is a well-known strategy for reducing risk. But some sponsors use “cheats” to hide what they’re really doing. And some investors allege that a recent Northwest Sustainable Properties deal on CrowdStreet (which is spectacularly imploding) was an egregious offender.

(Usual disclaimer: I'm just an investor expressing my personal opinion and am not an attorney, accountant nor your financial advisor. Consult your own financial professionals before making any financial decisions. Code of Ethics: To remove conflicts of interest that are rife on other sites, I/we do not accept ANY money from outside sponsors or platforms for ANYTHING. This includes but is not limited to: no money for postings, nor reviews, nor advertising, nor affiliate leads etc. Nor do I/we negotiate special terms for ourselves in the club above what we negotiate for the benefit of members. Info may contains errors so use at your own risk. See Code of Ethics for more info.)

Warren Buffett is one of the most famous and successful investors in the world. And he says he won’t invest in any deal unless the sponsor’s also willing to put their own money at risk and co-invest alongside him.

Buffet calls this “skin in the game.” And he says it’s crucial, because without it, the sponsor is misaligned with him (and will do things he doesn’t want and at his expense). So, skin in the game forces the sponsor to act in the interests of the investor and reduces investor risk.

The “dirty secret” of the real-estate industry

Unfortunately, many real estate deals come with plenty of additional opportunities for sponsor misalignments.

Paul Kaseburg is an experienced real-estate operator who's been seated on both sides of the table on over $2 billion worth of real estate deals. And he calls this the “dirty secret” of the industry.

The problem is that sponsors who take higher than normal sponsor compensation usually market this as a great benefit that aligns themselves better with investors. “I only get paid well, if you do well!” is the usual pitch. But in reality, it can financially incentivize them to engage in riskier behavior with investor money.

Here’s an example of a generous double-level waterfall structure (which some sponsors use):

The problem area is in yellow area on the right.

After a sponsor achieves a modest return, every fraction of a percent increase causes the their profit to skyrocket to the moon (i.e. exponentially). And the investor doesn’t get this benefit and plods along the same as before (linearly).

So this “jackpot” structure financially incentivizes the sponsor to push the risk envelope to get into that exponential state. This usually means engaging in riskier behavior like increasing debt (i.e. increased risk of default), taking floating rate (i.e. increased interest rate risk), shorter term loans (i.e. increased refinance risk), closing on deals that don’t pencil-out conservatively etc. And the investor isn't rewarded more for adding this risk on top (and is receiving the same linear return, as if no additional risks were being piled-on).

Beauty (or ugliness) is in the eye of the beholder

Now, many aggressive investors have no problem with this.

After all, they’re most interested in deals that have the highest projected returns. And pushing the risk envelope is usually the only way to structure a deal to do this. So many of these types of investors happily sign on for lots of these types of deals.

At the same time, every investor is different because each comes from a unique financial situation, has unique financial goals, and has a unique risk tolerance. And something that one investor thinks is great will look terrible to another and vice versa.

I’m a conservative investor and my number one concern is preventing loss and preserving principal. And since a single major loss will wipe out all the gains from many other successful investments, I feel it’s counterproductive to try to chase the highest projected returns. So to me the above alignment issue is potentially horrifying.

And if I were to be involved in a real estate transaction like the above, I would at least want to be on the other side of the table from the investor (in other words owning a GP stake in the sponsor and getting exponential reward to compensate for the extra risk of a disaster).

But usually that option isn’t available. And the only choice is to invest as a typical limited partner investor (or nothing at all).

So like Buffett, I typically won't touch any investor/LP stake without significant sponsor skin in the game.

And by the way, I also try to avoid double waterfall deals, and any deal where the sponsor is compensated much more than average.

Looking at skin in the game

There are many ways to measure percentage of skin in the game (co-investment). I measure it by dividing the sponsor’s true skin in the game ($) by the total equity ($). And I personally want to see at least 5 to 10%.

Occasionally, I’ll accept less from a newer sponsor… as long as I feel the amount they’re putting at risk would be considered a lot of money to them, if they lost it. But generally, I don’t like investing in newer sponsors. And that’s because I usually require my sponsors to have a full real estate cycle of experience (and with little to no investor money lost).

Again, other investors use different methods and have different requirements. And more aggressive investors will strongly disagree with me and prefer newer sponsors (because they often also come with higher projected returns).

Skin in the game “cheats”

Complicating things is the fact that some sponsors use "cheats" that overinflate their skin in the game.

For instance, investors who put their money into a Northwest Sustainable Properties deal that is currently imploding, allege that this happened to them. The River Frontier deal was marketed on the CrowdStreet platform. And the offering claimed it would have an eye-popping (and some might say “highly unusual to the point of almost being implausible"?) sky-high 26.8% sponsor co-investment:

And some investors claim they were very impressed by this. The deal raised all the money it needed and closed. Unfortunately, investors claim that since then, things have gone horribly wrong. They allege that they recently received a letter from the sponsor with the worst possible news. The property can't make it's debt payments, and they’re expected to take a catastrophic, punch-in the-gut total loss (i.e. -100% return).

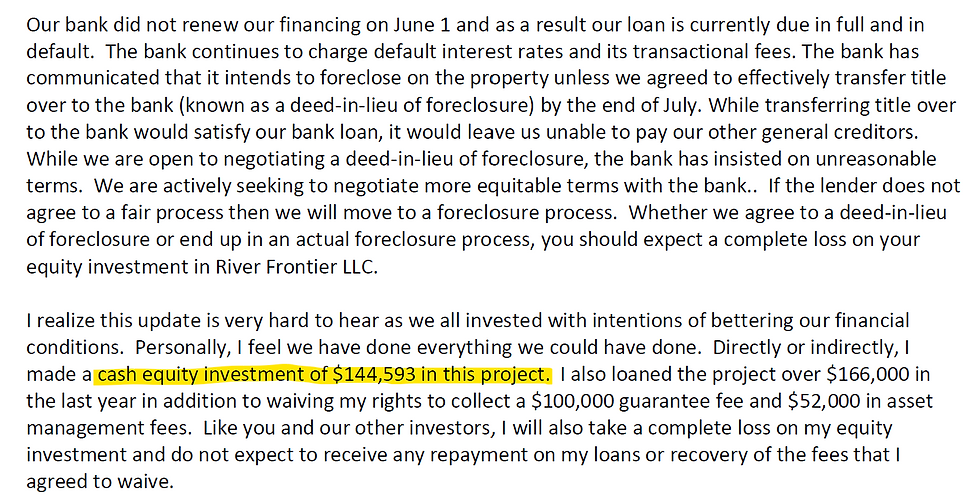

And investors say that this would have been bad enough on its own. But what surprised them even more is that the sponsor attempted to “make them feel better” and revealed this:

What happened to the claimed $950,000 of sponsor co-investment?

A $144,593 sponsor co-investment would reduce the actual skin in the game from a breathtaking 26.8% to a measly 4%. So investors claim they were shocked and flabbergasted.

Where is the missing money?

Investors allege they scoured the legal documents, and claim it says the following:

Who are the mystery parties? Ultimately, the names are redacted, so it doesn’t say. But according the manager, we do know the important point: that the money didn’t come from him.

Also, experienced investors know that some sponsors use a well-worn “cheat” to inflate their sponsor co-investment. And they will include other investors… whom they will sometimes claim to be “family and friends.” Some will even euphemistically use the name “friends” to mean early investors. And most will justify this by saying: “Look, I would never let down my own friends and family, would I?” The big problem is that none of these types of investors have any legal management control over the deal. So they are clearly not the sponsor (who does have that control).

And so it’s highly inaccurate to call this money “sponsor co-investment." It’s clearly not.

In this particular case, investors have had to play a guessing game as to what truly happened. But either way, the manager revealed that his true sponsor co-investment was many times less than what investors expected (and what the offering claimed it would be).

And some investors say that if this had been accurately disclosed from the beginning, then they never would have invested.

Stripping out the over-inflated hype

This is why I personally take initial claims of skin in the game with a huge grain of salt. And I always dig in with additional questions, like:

What portion of this is coming from parties who have legal management control over the entity?

Is all of this coming from cash and on the same terms as for all other investors? If not, what are the details?

Is any of that money coming from a GP co-investment fund? If not, have you ever taken money from a GP co-investment fund? Do you intend to do so in the future?

In the end, there's no way to be 100% sure that any investment isn't a fraud (both in public markets and private ones). And the same idea applies to skin the game. Still... many people find buying car insurance is useful... even though it doesn't guarantee avoiding an accident. So, I personally find asking these types of additional due-diligence questions to be very useful.